Zero.Zero 2012

Related Links: view complete Zero.Zero brief as a PDF; view economic and revenue projections here; view Zero.Zero Executive Summary here; view Zero.Zero media release here; go to Zero.Zero home page; Report Card on RI Competitiveness

Background

In January of 2013, Massachusett’s Governor, Deval Patrick, proposed cutting the Bay State sales tax from 6.5% to 4.5%. This could be a devastating blow to Rhode Island’s already fragile economy.

Competition among states is real, and it is clear that the Ocean State is losing its bid for people, money, businesses, and jobs. Public policy is not enacted in a vacuum; when a state makes changes to its policies — whether dealing with taxes or regulations — its overall image and competitiveness are affected.

In order to generate money to pay for Rhode Island’s growing appetite for public spending, the state has been forced to acquire new sources of revenue via tax and fee increases. This failed culture of trying to tax our way to a better future has steadily degraded the state’s ability to maintain and attract the critical human and capital resources required to grow its economy.

The RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity’s recently released Report Card on Rhode Island Competitiveness demonstrates how the state’s burdensome tax structure has weakened its competitive status versus other states in securing the necessary building blocks for a vibrant economy. The report card grades both the state’s overall tax burden and its business climate as Fs. In fact, 27 of 49 areas are graded F. With proposals to raise taxes even higher, fiscal irresponsibility and fears of a double-dip recession in the state persist.

Rhode Island needs a reboot. Our state must reverse course and embark on a different path that will restore prosperity, beginning with a firm statement of its future intentions. A new culture must take root — one that appreciates the power of unleashing, rather than restricting, the great potential of individuals and businesses.

Many states across the country have embarked on aggressive tax-reform paths designed to foster economic growth. States with no income tax outperform their high-tax counterparts across the board — in gross state product growth, population growth, job growth, and, perhaps shockingly, even tax-receipt growth. Over the last decade, on net, more than 4.2 million individuals have moved out of the ten states with the highest state and local tax burdens (measured as a percentage of personal income). Conversely, more than 2.8 million Americans migrated to the ten states with the lowest tax burdens.

Our New England sister, New Hampshire, has a significantly higher-performing economy as a result of its dramatically lower overall tax burden, providing the Ocean State with ample empirical evidence. If Rhode Island is to keep pace, it too must embrace market-driven policies that acknowledge the importance of incentives and disincentives as well as the reality of taxpayer mobility.

In short, Rhode Islanders must decide whether they want to stay on their current path and simply hope for change or should boldly shift gears and move toward a new path of fiscal sustainability.

Policy Proposition: Eliminate the State Sales Tax

In seeking the single most-effective tax reform providing the most-immediate impact to the most-pressing problem in the Ocean State — jobs — the Center for Freedom & Prosperity determined that the state sales tax would be an auspicious place to start. Mainly, the more mobile the factors being taxed, the larger and more immediate the response to tax rate changes. Consumer shopping habits are highly mobile, and cross-border shopping is especially convenient for Rhode Islanders and their neighbors.

While Rhode Island requires broad reform, making tax policy more efficient across multiple categories, our Center simulated and projected the economic effect if Rhode Island were to follow New Hampshire’s proven path and completely eliminate the state sales tax. With any significant reduction in the state sales tax, a few important benefits would arise for the Ocean State:

- Hundreds of millions of dollars would be put back into the state economy.

- Tens of thousands of jobs would be created.

- Municipalities would collectively realize a windfall of tens or hundreds of millions of dollars.

- Gross domestic (state) product would increase by billions of dollars.

- State population, and the state tax base, would increase by thousands of people.

- State revenue losses would be less than static expectations because of the positive and “dynamic” economic effects that would be realized.

In short, Rhode Islanders’ decision is whether or not increased jobs, increased GDP, economic growth, and increased revenue for our cities and towns are worth some reduction in state spending.

Analysis

Problems with the Retail Sales Tax

Unfortunately, there are so many problems with Rhode Island’s tax code that it is almost impossible to know where to begin correcting them. There are simply too many high taxes in the Ocean State.

As an overriding goal, Rhode Island needs to start pruning the tax tree, and the best starting point is the single tax that, in the aggregate, is the most damaging to Rhode Island’s overall economy: the retail sales tax. There are several reasons that the sales tax is especially troublesome.

1. The general assumption that broadening the sales tax base is always a good idea is flawed.

The retail sales tax in the United States arose in response to the economic damage created by the gross receipts tax (GRT), which was more prevalent a century ago. The tax base of the GRT is the total receipts of a business, which maximizes the economically destructive “tax pyramiding” through the entire production structure of the economy.

To fix this problem, exemptions were created to transform the GRT into a retail sales tax that more resembled a consumption tax. However, due to the problem of “dual use,” whereby a good or service can be used for either business or personal reasons, exemptions have proven to be a crude and often ineffective way to create a pure consumption tax. Simply eliminating exemptions, especially on services, would only serve to rebuild the GRT Frankenstein piece by piece.

A study by the Council on State Taxation explains, “The current state and local sales tax differs from a true or ideal retail sales tax. A true retail sales tax would impose a uniform tax only on consumption — all goods and services sold to households — but would not impose any tax on business purchases of intermediate goods and services. The current sales tax system imposes over $100 billion of taxes on business purchases of business inputs and investments. This type of tax has significant adverse state economic development implications.”

The study found that 49.2 percent of Rhode Island’s sales tax is paid by businesses — higher than the national average of 42.8 percent.

2. The sales tax is a tax on investment.

Since the retail sales tax can never be fully eliminated on business inputs, the sales tax is ultimately a tax on investment. It is especially detrimental to the manufacturing and construction industries when their materials costs are subject to the sales tax. That raises the cost not only to the final consumer, but also to the companies themselves, since their suppliers are subject to the same tax on their materials. The end result is less money available for future investments, compounding over time.

In fact, Dr. Mark Crain, using a rigorous econometric analysis, found that “states suffer a substantial penalty for levying a marginal sales tax rate that is high in relation to other states. Of course, the reverse also applies. Substantial economic benefits redound to states with relatively low marginal sales tax rates … intuitively, the impact of the sales tax is analogous to a general, broad-based increase in the cost of production.”

3. The sales tax promotes consumer mobility.

Another negative aspect of the sales tax is that consumers are mobile and can easily shop online or in lower-tax jurisdictions — especially in Rhode Island, which not only is the smallest geographic state in the country, but also has the highest sales tax in the region. As a result, cross-border and Internet shopping are undermining the viability of the sales tax.

Studies show that New Hampshire, which does not have a sales tax, economically benefits from cross-border shopping from neighboring Maine and Vermont. In Maine, retail sales could be as much as $2.2 billion higher per year along the border if Maine had the same level of retail sales as New Hampshire. In Vermont, retail sales could be as much as $540 million higher per year, with an additional 3,000 more retail jobs.

Dr. Roger E. Brinner and Dr. Joyce Brinner find that sales tax–induced cross-border shopping can have broad negative effects: “a 1% point increase in the sales tax rate can cut about 2.6% from state output growth over a decade … consumers choose their buying locations to find relative bargains; if they can escape a tax by hopping across a nearby border to buy goods with lower excise or sales taxes, they will do so. Many other studies have found strong evidence of cross-border retail impacts, and these simple regressions confirm the statewide damage than can be caused.”

For these reasons, elimination of Rhode Island’s sales tax can be supported as a solid public policy option. However, it is important to note (given that Rhode Island’s overall tax burden grade is an F) that there are other tax changes that must be considered as part of a larger tax reform policy for the Ocean State.

Positive Economic Impact

If the state retail sales tax were to be eliminated, the Ocean State would realize multiple economic benefits before the new economic equilibrium has been reached. As projected by RI-STAMP, our economic modeling tool, Rhode Island would see the following:

- Over 21,000 new private sector jobs, reducing unemployment by over three points

- Up to $160 million in additional annual tax revenue to cities and towns

- An additional $1 billion available to spend in the state’s economy

- An increase of over $500 million in tax receipts

- Almost $500 million in new capital investment in the state

Is the Tax Cut Revenue Neutral?

Not quite. The state of Rhode Island would indeed see lower net receipts from elimination of or reductions in the state sales tax. However, net losses would not be as much as most would anticipate using a static (straight-line) calculation. There are three primary reasons that the dynamic effect would greatly mitigate actual revenue losses:

- A lower retail sales tax would spur additional retail sales. With increased in-state and cross-border shopping as a result, the state would be taking a smaller sales tax slice, but from a bigger pie. Under a four-year phase-out of the sales tax, this new revenue would pay for about 20% of the anticipated sales tax losses in the first three years.

- Increased receipts from other taxes. With the personal and business tax base expanded because of the new job creation, and with increased levels of economic activity in the state, receipts from other taxes and fees would pay for over 50% of the anticipated sales tax losses. Such receipts would come from projected increases in receipts from personal income taxes, corporate taxes, cigarette taxes, and others.

- Administrative costs. The state bears the full cost of enforcing the sales tax. If the state sales tax is completely eliminated, several dozens of state jobs dealing with collection and enforcement of the sales tax could be eliminated each year during the phase-out period. With 207 full-time equivalents (FTEs) currently proposed for fiscal 2013 and a total budget of about $21.3 million, the state’s Division of Taxation may eventually be able to reduce its budget by approximately one-third. These personnel savings would compensate for an additional 5–6% of the revenue losses in the first three years. It is also anticipated that these jobs could be absorbed into the new growth economy.

Other Benefits to the Economy and Implementation

Separate from the question of state revenue, the issue of sales tax compliance costs is a serious one for most businesses. Sales taxes are particularly onerous, since the taxability of goods and services can vary greatly — even within a single business establishment — and virtually all businesses would save administrative and/or service costs by not having to categorize, collect, track, and remit sales tax revenue to the state. These savings are not estimated in this report but represent a benefit in addition to those conveyed in the RI-STAMP projections.

The Center for Freedom & Prosperity makes no specific recommendation as to how to implement elimination of the state sales tax. (See Attachment A for a schedule of projected revenue and economic impact measurements.) Rather, the primary goal is to demonstrate that cutting taxes provides an alternative path when considering how to put Rhode Island’s economy back onto a solid competitive footing.

Actual implementation of this plan will depend largely on the political willpower of public officials and citizens, and their willingness to embrace a new culture that seeks to enhance the state’s competitiveness instead of seeking to perpetuate the status quo. Options for implementation include:

- Four-year phase out of the state sales tax. Pros to this approach include less-dramatic year-to-year revenue losses and associated budget cuts. Cons include “cold feet syndrome,” whereby legislators may reverse course at some point during the phase-out period (as they have done with the planned car tax phase-out, not to mention income tax reforms like the flat tax) and the opportunity for neighboring states to respond before the full effects of the sales tax elimination actually take place.

- Immediate elimination of the state sales tax. Pros to this approach include a more immediate economic impact and realization of new jobs, with less chance for competing states to react. Cons include the need for larger near-term budget cuts and the difficulty of projecting actual revenue one, two, and three years out.

Balancing the Budget

It is expected that the four-year phase-out would be the most politically viable option. With the sales tax elimination potentially paying for up to 75% of itself in the early years, the important question becomes how to budget for the loss of the remaining 25% in order to balance the state budget on an ongoing basis.

Some combination of the following budget items could make up for much of this difference:

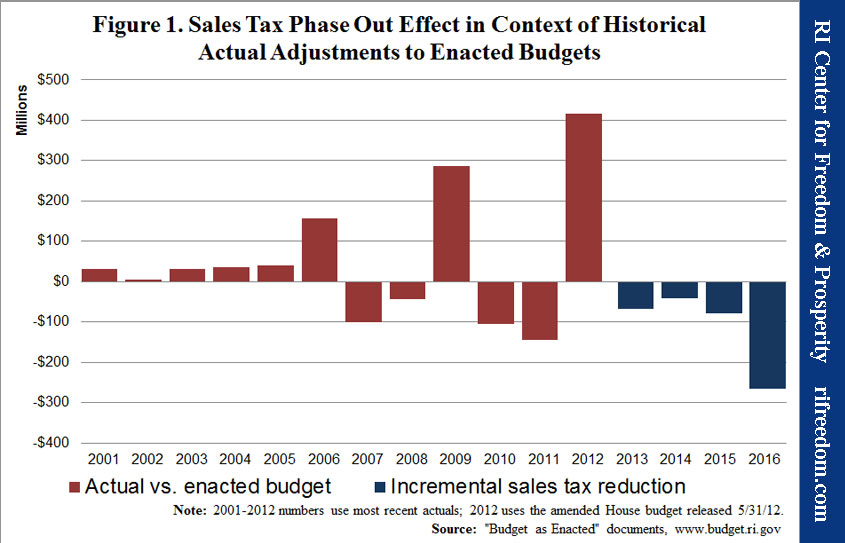

- Control budget growth. The least painful option would be to control budget growth during the phase-out years. As Figure 1 illustrates, a four-year phase-out of Rhode Island’s sales tax would be no more dramatic than the adjustments that the state government has been making to its enacted budgets year after year.

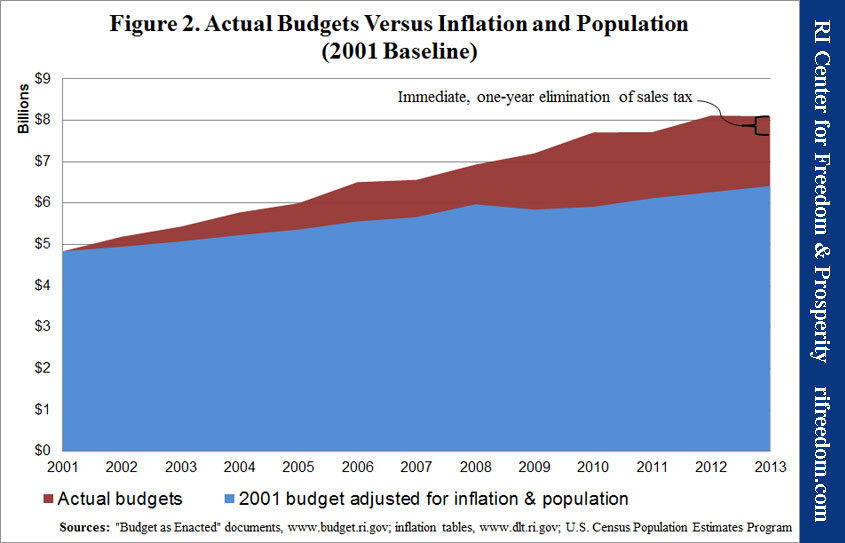

- Furthermore, the state’s budget has been growing so much more quickly than inflation and population changes alone would justify that the General Assembly’s proposed 2013 budget is 26.24% larger than it would be using a 2001 baseline. Figure 2 shows that even immediate full elimination of the sales tax would represent a relatively minor adjustment toward that level of spending, returning state government to a budget a little below its 2011 level. Once again, New Hampshire provides an example — that government growth can reverse — with actual policy changes implementing over $600 million in cuts to its 2013 budget.

- Eliminate corporate welfare. Eliminating approximately $50 million per year in systematized corporate handouts, in addition to slush funds like the $125 million in loan guarantees RIEDC was authorized to risk on special cronyism deals with connected companies, would also go a long way toward mitigating any remaining budget cuts that may be necessary to pay for elimination of the state sales tax.

- Apply the FY12 $81.4 million budget surplus. If we are serious about revitalizing our state in the manner described in this brief, we must immediately prioritize spending and revenue toward this end. There is no time like the present. This $81.4 million would cover over one year of the budget cuts necessary to pay for elimination of the sales tax.

- Reduction in government jobs. The administrative savings of 75 jobs, or about $7 million per year as described previously, can also help pay for some of the cost. As collection and enforcement of the current state sales tax will eventually no longer be needed, certain savings in this area can be realized.

Conclusion

Recent performance indexes make it clear that Rhode Island is on the wrong path, and only dramatic reform can produce dramatic results. While a broad package of tax and regulatory reform is required, the elimination of the state sales tax would mark a bold — yet viable — change of course.

When presented with the dire economic circumstances currently facing the Ocean State, all legitimate options to improve our state must be considered. While the elimination of a tax that provides approximately $1 billion in revenue to the state each year may seem extreme at first glance, legislators and the general public should seriously consider the facts, projections, and theories discussed in this report.

WHAT IS RI-STAMP?

Economic Modeling: There is a common and fundamental miscalculation when it comes to projecting the effects of tax policy on tax receipts. Too often, the more short-sighted and simplistic static (straight-line) calculation is utilized, when in reality the more complex dynamic impact should be evaluated. The downstream ripple effects of tax policy on various aspects of the economy and upon other tax receipts and fees are rarely discussed or attempted to be quantified, either at the state or municipal level. RI-STAMP seeks to fill this gap.

Developed by the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University, RI-STAMP is a customized, comprehensive model of the RI state economy, designed to capture the principal effects of city tax changes on that economy. In general STAMP is a five-year dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) tax model. As such, it provides a mathematical description of the economic relationships among producers, households, government and the rest of the world. It is general in the sense that it takes all the important markets and flows into account. It is an equilibrium model because it assumes that demand equals supply in every market (goods and services, labor and capital); this is achieved by allowing prices to adjust within the model (i.e., prices are endogenous). The model is computable because it can be used to generate numeric solutions to concrete policy and tax changes. And it is a tax model because it pays particular attention to identifying the role played by different taxes.

RI-STAMP has been accurate in projecting the effects of recent changes to tax policy in Massachusetts and New York City, among other locales.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!