Zero.Zero 2013

Rhode Island families are being torn apart. Parents, children, and siblings are being driven out of the state in search of good work and a more reasonable cost of living.Reducing the state sales tax from 7.0% to 0.0% will bring shoppers and retail and construction jobs back to our state and keep our families and businesses intact and at home here in the Ocean State.

Related Links:

- Alternative and 3% sales tax reform scenarios;

- 2013 Zero.Zero brief as a PDF

- Feb 25 Media Release: Go to Zero.Zero home page

- Report Card on RI Competitiveness

- GoLocalProv Feature Article (Feb 2013)

- Stenhouse on RI-NPR radio; Unemployment Above 25% for Rhode Island Youth

Executive Summary

Rhode Island families are being torn apart. Parents, children, and siblings are being driven out of the state in search of good work and a more reasonable cost of living. Businesses struggle in an uncompetitive business climate. With one of the worst jobs outlooks and population trends in the entire nation, the Ocean State is in need of a game-changing policy reform to restore financial security and hope for a brighter future for our fellow citizens.

Reducing the state sales tax from 7.0% to 0.0% will bring shoppers and retail and construction jobs back to our state and keep our families and businesses intact and at home here in the Ocean State.

Boost for Our Economy:

- Around 25,000 new jobs created, with fewer people dependent on public assistance to get by

- Nearly an additional $1 billion of their own money left in Rhode Islanders’ pockets to spend in the state’s economy

- A $150 million annual revenue gain for cities and towns

- An increase of more than half-a-billion dollars in other tax receipts and fees due to increased economic activity

- Savings for business: zero compliance costs and headaches; reduced costs for supplies and services

New Economy Will Provide Real Savings and Increased Opportunities for Families:

- 7%+ lower net cost for many products and services for RI shoppers, such as restaurant dining, liquor, appliances, and other household items

- Up to $400 million in B2B sales tax savings potentially passed on to consumers, reducing the prices of many products and services, some not subject to the sales tax, such as food, clothing, and auto insurance

- $60+ million back in the pockets of low income RI families, who currently bear one of the top 10 tax burdens for their income category in the entire nation; $450+ million savings for middle-income families

- Increased chance of upward mobility as a result of across-the-board wage hikes and new job opportunities

RI’s Government Spending Problem and Failed Budget:

Reducing government spending will strengthen the Rhode Island economy, increasing opportunities for our children and improving the quality of life for our families for generations to come.

Rhode Island’s budget has failed its citizens. Its burdensome level of spending and taxation has strangled economic growth, costing us tens of thousands of jobs, and has resulted in far too many “last place” rankings. Excess and wasteful spending must be cut from the budget; a lower overall tax burden will restore jobs and economic vitality.

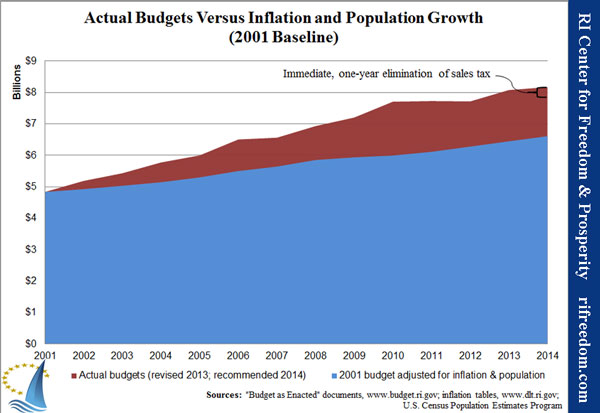

- In the last 12 years, state spending has increased 25% more than the combined inflation and population growth — creating almost $1.6 billion in excessive or wasteful spending (see Chart 1).

- Rhode Island’s population is 1.1 million, with a proposed budget of about $8.2 billion, $7,781 per person. New Hampshire’s population is 1.3 million, with a proposed budget of about $5.4 billion, $4,078 per person.

Background

Competition between states is real. And it is clear that the Ocean State is losing its bid for people, money, businesses, and jobs. Public policy is not enacted in a vacuum; when a state makes changes to its policies — whether dealing with taxes or regulations — its overall image and competitiveness are affected.

In order to generate money to pay for Rhode Island’s growing appetite for public spending, the state has been forced to acquire new sources of revenue via tax and fee increases. This failed culture of trying to tax our way to a better future has steadily degraded the state’s ability to maintain and attract the critical human and capital resources required to grow its economy.

The RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity’s annual Report Card on Rhode Island Competitivenessdemonstrates how the state’s burdensome tax structure has weakened its competitive status versus other states in securing the necessary building blocks for a vibrant economy.[1] The report card grades both the state’s overall tax burden and its business climate as Fs. In fact, in the 2013 Report Card, to be released soon, 32 of 51 areas are graded F. With proposals to raise taxes even higher, fiscal irresponsibility and fears of a double-dip recession in the state persist.

Rhode Island needs a reboot. Our state must reverse course and embark on a path that will restore prosperity, beginning with a firm statement of its future intentions. A new culture must take root — one that appreciates the power of unleashing, rather than restricting, the great potential of individuals and businesses.

States across the country have embarked on aggressive tax-reform paths designed to foster economic growth. The income tax is more typically the target of such reforms, because states with no income tax generally outperform their high-tax counterparts across the board — in gross state product growth, population growth, job growth, and, perhaps shockingly, even tax-receipt growth. In Rhode Island’s case, geographic size and dire need support targeting the sales tax instead.

Focusing on the sales tax, however, should not be done as a trade for raising any other taxes. Over the last decade, on net, more than 4.2 million individuals have moved out of the ten states with the highest state and local tax burdens (measured as a percentage of personal income). Conversely, more than 2.8 million Americans migrated to the ten states with the lowest tax burdens.[2] The Ocean State needs to bring down its total burden.

Our New England neighbor, New Hampshire, provides ample empirical evidence, with a significantly higher-performing economy as a result of its dramatically lower overall tax burden. And now, with the prospect of a sales tax border-war with Massachusetts, if Rhode Island is to keep pace, it too must embrace market-driven policies that acknowledge the reality that tax incentives and disincentives do affect taxpayer and shopper mobility.

In short, Rhode Islanders must decide whether they want to stay on their current path and simply hope for change or boldly shift gears and move toward a new path of fiscal sustainability and economic growth.

Policy Proposition: Eliminate the State Sales Tax

In seeking the single most-effective tax reform providing the most-immediate impact to the most-pressing problem in the Ocean State — jobs — the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity determined that the state sales tax would be an auspicious place to start. Mainly, the more mobile the factor being taxed, the larger and more immediate the response to tax rate changes. Consumer shopping habits are highly mobile, and cross-border shopping is especially convenient for Rhode Islanders and their neighbors.

While Rhode Island requires broad reform, making tax and regulatory policy more efficient across multiple categories, the Center simulated and projected the economic effect if Rhode Island were to follow New Hampshire’s proven path and completely eliminate the state sales tax. Any significant reduction in the state sales tax would yield important benefits for the Ocean State:

- Hundreds of millions of dollars would be put back into the state economy.

- Tens of thousands of jobs would be created.

- Municipalities would collectively realize an inflow of tens or hundreds of millions of dollars.

- Gross domestic (state) product would increase by billions of dollars.

- State population, and the state tax base, would increase by thousands of people.

- State revenue losses would be less than static expectations because of the positive and “dynamic” economic effects that would be realized.

In short, Rhode Islanders’ decision is whether or not increased jobs, increased GDP, economic growth, and increased revenue for our cities and towns are worth some reduction in state spending.

Analysis

Problems with the Retail Sales Tax

Unfortunately, there are so many problems with Rhode Island’s tax code that it is almost impossible to know where to begin correcting them. There are simply too many high taxes in the Ocean State. A quick review of ten different types of taxes across all New England states shows that Rhode Island doesn’t offer the lowest or second lowest rate on any of them and is worst or second worst in the region on more than half.[3]

As an overriding goal, Rhode Island must start pruning the tax tree, and the best starting point is the tax that, in the aggregate, is the most damaging to the state’s overall economy: the retail sales tax. There are several reasons that the sales tax is especially troublesome.

1. The general assumption that broadening the sales tax base is always a good idea is flawed.

The retail sales tax in the United States arose in response to the economic damage created by the gross receipts tax (GRT), which was more prevalent a century ago. The tax base of the GRT is the total receipts of a business, which maximizes the economically destructive “tax pyramiding” through the entire production structure of the economy.

To fix this problem, exemptions were created to transform the GRT into a retail sales tax that more resembled a consumption tax. However, due to the problem of “dual use,” whereby a good or service can be used for either business or personal reasons, exemptions have proven to be a crude and often ineffective way to create a pure consumption tax. Simply eliminating exemptions, especially on services, would only serve to rebuild the GRT Frankenstein piece by piece.

A study by the Council on State Taxation explains, “The current state and local sales tax differs from a true or ideal retail sales tax. A true retail sales tax would impose a uniform tax only on consumption — all goods and services sold to households — but would not impose any tax on business purchases of intermediate goods and services. The current sales tax system imposes over $100 billion of taxes on business purchases of business inputs and investments. This type of tax has significant adverse state economic development implications.”

The study found that 49.2 percent of Rhode Island’s sales tax is paid by businesses — higher than the national average of 42.8 percent.[4]

2. The sales tax is a tax on investment.

Since the retail sales tax can never be fully eliminated on business inputs, the sales tax is ultimately a tax on investment. It is especially detrimental to the manufacturing and construction industries when their materials costs are subject to the sales tax. That raises the cost not only to the final consumer, but also to the companies themselves, since their suppliers are subject to the same tax on their materials. The end result is less money available for future investments, compounding over time.

In fact, Dr. Mark Crain, using a rigorous econometric analysis, found that “states suffer a substantial penalty for levying a marginal sales tax rate that is high in relation to other states. Of course, the reverse also applies. Substantial economic benefits redound to states with relatively low marginal sales tax rates … intuitively, the impact of the sales tax is analogous to a general, broad-based increase in the cost of production.”[5]

A recent study of state-by-state business taxes, released by Ernst & Young and the Council on State Taxation, found that Rhode Island businesses pay about $400 million in sales taxes.[6]

3. The sales tax promotes detrimental consumer mobility.

Another negative aspect of the sales tax is that consumers are mobile and can easily shop online or in lower-tax jurisdictions — especially in Rhode Island, which not only is the smallest geographic state in the country, but also has the highest sales tax in the region. As a result, cross-border and Internet shopping are undermining the viability of the sales tax.

Studies show that New Hampshire, which does not have a sales tax, economically benefits from cross-border shopping from neighboring Maine and Vermont. In Maine, retail sales could be as much as $2.2 billion higher per year along the border if Maine had the same level of retail sales as New Hampshire.[7]In Vermont, retail sales could be as much as $540 million higher per year, with an additional 3,000 more retail jobs.[8]

Dr. Roger E. Brinner and Dr. Joyce Brinner find that sales tax–induced cross-border shopping can have broad negative effects: “a 1% point increase in the sales tax rate can cut about 2.6% from state output growth over a decade … consumers choose their buying locations to find relative bargains; if they can escape a tax by hopping across a nearby border to buy goods with lower excise or sales taxes, they will do so. Many other studies have found strong evidence of cross-border retail impacts, and these simple regressions confirm the statewide damage than can be caused.”[9]

For these reasons, elimination of Rhode Island’s sales tax can be supported as a solid public policy option. However, it is important to note (given that Rhode Island’s overall tax burden grade is an F) that there are other tax changes that must be considered as part of a larger tax reform policy for the Ocean State.

Positive Economic Impact

If the state retail sales tax were to be eliminated, the Ocean State would realize multiple economic benefits before the new economic equilibrium has been reached. As projected by RI-STAMP, our economic modeling tool, Rhode Island would see the following:

- Over 25,000 new private sector jobs, reducing unemployment by over five points

- Up to $150 million in additional annual tax revenue to cities and towns

- Nearly an additional $1 billion available to spend in the state’s economy

- An increase of nearly $600 million in other state tax and fee receipts

- Over $500 million in new capital investment in the state

Other Benefits to the Economy and Implementation

Separate from the question of state revenue, the issue of sales tax compliance costs is a serious one for most businesses. Sales taxes are particularly onerous, since the taxability of goods and services can vary greatly — even within a single business establishment — and virtually all businesses would save administrative and/or service costs by not having to categorize, collect, track, and remit sales tax revenue to the state. These savings are not estimated in this report but represent a benefit in addition to those conveyed in the RI-STAMP projections.

The Center for Freedom & Prosperity makes no specific recommendation as to how to implement elimination of the state sales tax. (See Attachment A for a schedule of projected revenue and economic impact measurements.) Rather, the primary goal is to demonstrate that cutting taxes provides an alternative path when considering how to put Rhode Island’s economy back onto a solid competitive footing.

Actual implementation of this plan will depend largely on the political willpower of public officials and citizens, and their willingness to embrace a new culture that seeks to enhance the state’s competitiveness instead of seeking to perpetuate the status quo. Options for implementation include:

- Immediate elimination of the state sales tax. Pros to this approach include a more-immediate economic impact and realization of new jobs, with less chance for competing states to react. Cons include larger near-term budget strain and difficulty projecting actual revenue one, two, and three years out.[10]

- Four-year phase out of the state sales tax.Pros to this approach include less-dramatic year-to-year revenue losses and associated budget cuts. Cons include “cold feet syndrome,” whereby legislators may reverse course at some point during the phase-out period (as they have done with the planned car tax phase-out, not to mention income tax reforms like the flat tax) and the opportunity for neighboring states to respond before the full effects of the sales tax elimination actually take place.

Balancing the Budget

Perspective on the Investment

With the actual introduction, this year, of legislation to completely eliminate the state sales tax, the Center is better able to assess the fiscal impact and to offer broad suggestions for balancing the state’s budget.

The guiding principle, here, is that Rhode Island is more than the sum of its state agency budgets; it is a regional society of people with their own dreams and intentions. A recent report from the liberal Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy (ITEP) rates Rhode Island poorly for the tax burden that it places on lower-income households, and the sales tax is largely to blame.[11] ITEP’s analysis says nothing of the cost to struggling families of the Ocean State’s stagnant economy and fading opportunities.

In that regard, the savings that the state government must find in its budget in order to eliminate the sales tax are best seen as an investment in the larger economy, made in a way that also increases the tax equity for which advocacy groups are continually calling. If the state of Rhode Island were to eliminate its sales tax on the first day of fiscal year 2014 (on July 1, 2013), the Center projects that the first-year investment that officials would have to balance would be $312.69 million, after the dynamic effects projected with RI-STAMP, or just 3.83% of the governor’s proposed budget of $8.17 billion.

Chart 1 shows that percentage in the context of the budget trends of the Rhode Island government. The blue area on the chart is what the budget would have been had it merely increased along with inflation and population after 2001. The red area is the amount that the budget actually increased above and beyond that baseline. For 2014, the governor’s proposed budget is 25.28% larger than inflation and population would have justified.

The black bracket illustrates the size of a $312.69 million investment in the sales tax elimination. As can readily be seen, returning the budget to its actual level during fiscal year 2012 — last year — would more than cover the investment. However, both the language of the legislation submitted and the fact that the budget wouldn’t actually be reduced by the full investment all at once make even Chart 1’s small adjustment appear overly dramatic.

The relevant bills currently under consideration in the General Assembly, H5365 and S0246,[12] would eliminate the 7% sales tax as of October 1, 2013. That would allow for reduced consumer prices during the holiday shopping season, but it would still capture the very strong sales-tax tourist months of the summer. Taking that delay into account and applying the dynamic growth of other taxes, as predicted by RI-STAMP, to the governor’s revenue assumptions, the Center projects the actual cost of the sales-tax elimination in the first fiscal year to be $236.33 million.

In this context, “dynamic” means that the estimates do not simply eliminate the projected revenue for the tax in question. That would be a “static” analysis. Rather, a dynamic analysis takes into account the effect that changing the tax structure will have on the economy and, therefore, on other taxes and revenue. This is especially important with the sales tax, because the statewide reduction of final retail prices immediately amplifies the market, and shoppers can change their habits with no preparation. The effects of taxes, as on income, that focus on production, rather than consumption, begin with changes in the behavior of people building markets, which takes time and is hindered by Rhode Island’s burdensome regulatory regime.

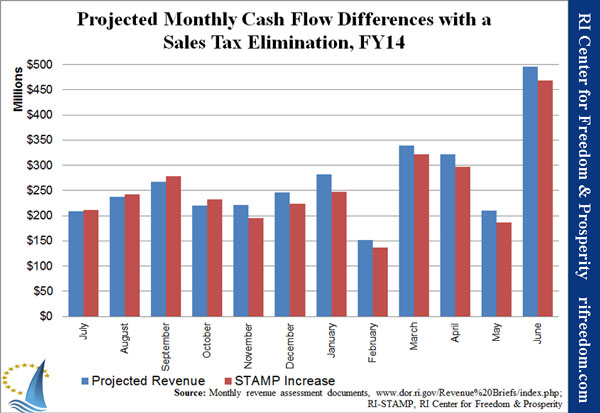

Chart 2 shows a month-by-month comparison of the state’s cash flow using the governor’s projected revenue with the Center’s projections using Zero.Zero. Initially, as employers and supporting businesses prepare for the dramatic improvement of their competitive standing, the first several months are actually higher than official estimates, and then the investment in the sales tax elimination phases in over the remainder of the year.

To arrive at these numbers, we averaged the adjusted monthly collections from each revenue source as a percentage of the annual totals for fiscal years 2011 and 2012. For the projected estimates, we applied those monthly percentages to the governor’s fiscal year 2014 projections. For the sales-tax-elimination estimates, we aligned Rhode Island’s categories as closely as possible with the categories used in RI-STAMP, calculated the average monthly increase or decrease for each, and applied that to the governor’s projections.

The sales and use tax applies to four months for cash flow, because each month’s revenue is from activity the previous month, but because July revenue is attributed to the previous fiscal year, it does not reduce the total investment required for Zero.Zero. We assumed that there would be a 50% reduction in expected September shopping deferred until after the sales tax elimination. Similarly, we assumed that the state’s take from motor vehicle fees would see a 25% reduction, commensurate with fewer vehicle sales that month.

For the income tax, we assumed that July would see one-tenth of the monthly projected STAMP increase, as companies begin preparing for increased retail volume and related economic growth. For August, the assumption was one-fifth of the projected STAMP increase, and for September, it was one-half.

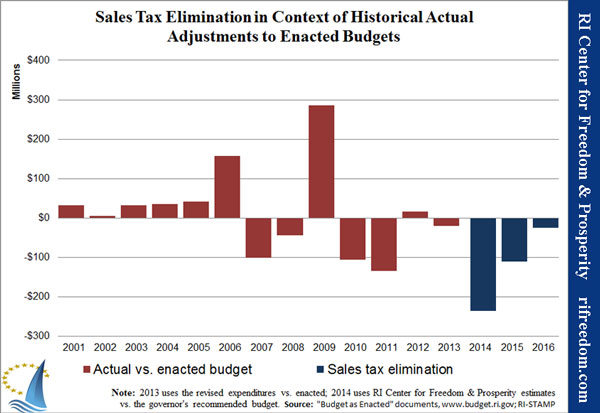

Chart 3 puts the budget adjustments that would be necessary in order to eliminate the sales tax in the context of the midyear adjustments that the Rhode Island state government makes to its enacted budgets midyear every year. Through 2012, the number compared with the relevant enacted budget is the actual total expenditure that the state ultimately made for that year. For 2013, the most recent revised budget is compared with the enacted budget. For 2014, the Center compared its Zero.Zero estimates with the governor’s recommended budget, and for 2015 and 2016, the reduction assumes that the government lowered its baseline spending in the previous year.

The chart shows that the amounts of the investments necessary for Zero.Zero are not outrageously greater than the adjustments that Rhode Islanders’ economic hardships have forced on the state government. A second key takeaway from Chart 3 is that the budget will have effectively absorbed the elimination of the sales tax by 2016.

A Strategy for the Change

Any substantial change of government policy, particularly if it has to do directly with budgetary and economic matters, should be made with good-faith estimation of the effects. Such estimations must also be understood as what they are — predictions about the future — with some strategy for accommodating unexpected outcomes.

In the case of the proposed legislation to eliminate the sales tax, the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity suggests a three-tiered approach. The numbers presented are necessarily preliminary, leaving finer details to the professionals who work with the state budget and the elected officials who oversee their activities.

The Initial Investment

The first dollar amount that must be addressed is the approximate $236 million investment that we project that the state government will have to make in the first year of Zero.Zero. Around one-third of that amount can be covered by opting not to spend the projected budget surplus of $79.3 million from this fiscal year on new programs. The governor’s recommended budget includes another $52.2 million in new expenditures from General Revenue that should be held.

Freezing the budget in this way would allow the state to free its people and its economy of the sales-tax burden for an initial government investment of $104.8 million. That is a small sum in comparison with the nearly two-thirds of a billion dollars that would remain in consumers’ pockets over the course of the year.

A large portion of that amount is likely to be found in outright waste and abuse already discovered in an investigation by Simpatico Software. U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform documents from 2012 suggest that waste and abuse account for a minimum of 10% of Medicaid spending.[13] Even 6% of the state’s contribution to assistance and grants for human services could amount to between $50 million and $80 million, depending what’s included.

Ending other assistance and grants programs targeted at corporations in the name of economic development could free up another $50 million.[14] Similarly, the nearly $90 million in overtime that the state of Rhode Island pays annually to its employees likely presents opportunity for tens of millions of dollars in savings.

Table 1 shows the necessary investment and lists some potential areas of easy savings.

Longer-Term Adjustments

The next dollar amount of concern is the roughly $350 million by which RI-STAMP projects the government of Rhode Island will have to adjust its total budget baseline in order to invest in Zero.Zero. As noted above, that figure is less than the amount that the governor’s proposal for fiscal year 2014 adds to the budget as it was in fiscal year 2012.

If the FY14 budget is frozen and the first-year savings found as described in the previous section, that would adjust the baseline by $236 million. The Center for Freedom & Prosperity estimates that the necessary adjustment to FY15 would therefore be around $110 million. Of course, the sooner the government finds and implements savings, the easier and more financially prudent the transition will be. Ultimately, the state will need to find a little bit more than 3% savings in its general revenue spending beyond its initial investment, which shouldn’t be an insurmountable task.

And beyond savings that could be found within the budget under any circumstances, the improved economy after eliminating the sales tax will come with its own savings, as fewer people require government assistance.

The Speed of Dynamic Change

It is important to acknowledge, while projecting revenue after the sales tax is eliminated, that the dynamic effects predicted by RI-STAMP derive from an “equilibrium model.” That means that the overall change in jobs and tax revenue is the effect on a single year of baseline data after the economy has adjusted to the new reality. That could take six months, or it could take 18 months. In other words, even if the projections are perfectly accurate, there is no guarantee that equilibrium will happen in a 12-month period, and there’s certainly no guarantee of even changes from month to month.

The predictions described in this report, therefore, require some argument for confidence that they are achievable. Unfortunately, no state that has implemented a sales tax has subsequently eliminated it, and even if there were some precedent, Rhode Island’s size, location, and back-of-the-pack economy make the state unique.

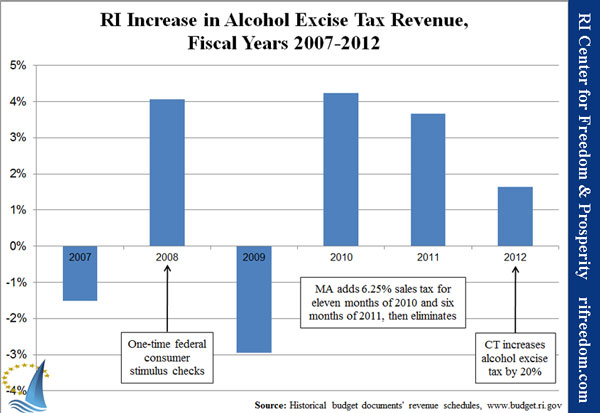

However, Massachusetts provided a small-scale case study when it applied sales tax to alcohol for a year and a half. Both Rhode Island and Massachusetts apply excise taxes to alcohol at the manufacture/distribution stage, and the two states’ rates are comparable. The states differ, however, in that Rhode Island also applies its 7% sales tax to alcoholic beverages.

Massachusetts changed that dynamic for a brief period. Effective August 2009 (one month into Rhode Island’s fiscal year 2010), the Bay State applied its 6.25% sales tax to alcohol, immediately leveling the playing field across the border between the two states — the inverse effect to a sales tax elimination in Rhode Island. Then, by means of a ballot question, Massachusetts voters undid the tax increase, effective January 2011.

The revenue from Rhode Island’s alcohol excise tax gives some indication of the effect on the industry, as shown in Chart 4. With the beginning of the recession halfway through FY07, alcohol tax revenue dropped 1.5% that fiscal year. In FY08, the Bush administration targeted large stimulus spending at consumers, and the 4.1% increase in RI alcohol tax revenue for that year is reasonably consistent with estimates of its overall effect.[15] The following year, growth returned to its negative trend, with alcohol tax revenue down 3.0%.

Massachusetts’s sales tax on alcohol was in effect for nearly the entire fiscal year of 2010, and Rhode Island’s excise tax revenue was up 4.2%. The next year, Massachusetts’s tax remained in effect throughout the summer and holiday seasons, and tax revenue was up 3.7% in Rhode Island.

In FY12, the RI revenue effects of a renewed disparity in sales tax on alcohol were muddied because Connecticut increased its alcohol excise tax 20% that year, which can be expected to have mitigated Rhode Island’s losses to some degree. Nonetheless, alcohol tax revenue in the Ocean State only increased 1.6%, and revised estimates for FY13 in the governor’s latest budget recommendation expect only a 1.1% increase for this year.

Anecdotal evidence translates this tax revenue picture into jobs. A liquor store owner in Central Falls tells the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity that his monthly year-over-year sales immediately rose, in some months by as much as 50-60%, in the first year of Massa-chusetts’s sales tax increase. Consequently, he increased hours for his part-time employees and hired an additional employee. When circumstances changed again in 2011, he cut hours and laid the new employee off.

According to the Rhode Island Division of Taxation, 31,754 businesses have the sales tax permits required to sell taxed goods and services in the state. Obviously, permit holders are diverse — ranging from sole proprietors who sell items as a hobby to major chain stores with many employees. But if two-thirds of them were to average just one additional employee each in FY14, they would meet the RI-STAMP projection for the retail sector.

A Fiscally Prudent Safety Valve

As acknowledged above, projections about revenue and savings are inherently speculative, but that is true whether political leaders take bold action to help Rhode Island’s economy grow or not. By the governor’s estimates, the state government faces a $377.8 million deficit in 2017 if it does nothing. That does not have to be the case, if the economy grows at a significantly faster pace.

Furthermore, there is no reason that the government should be the one organization in Rhode Island that never has to cut expenses, as opposed to merely limiting the amount that its spending increases. We would argue that the fortunes of the state government ought to be very closely related to the fortunes of the people whom it is supposed to represent.

Toward that end, the architects of the state budget should identify programs and expenditures that are not critical to the state government’s mission and/or that can be delayed with minimal effect. The month-to-month funding of those expenditures should then be made contingent upon the accuracy of the projections shown in Chart 2 above.

With a prioritized list of such spending, the state could prepare for the elimination of the sales tax in a way that:

- Makes a minimal, but credible, amount of actual cuts to the budget

- Ensures that shortfalls from the estimates affect the lowest priorities first

- Renews other spending to its budgeted level as the improving economy reaps rewards for the people of Rhode Island and, in turn, its government

Conclusion

Recent performance indexes make it clear that Rhode Island is on the wrong path, and only dramatic reform can produce dramatic results. While a broad package of tax and regulatory reform is required, the elimination of the state sales tax would mark a bold — yet viable — change of course.

When presented with the dire economic circumstances currently facing the Ocean State, all legitimate options to improve our state must be considered. While the elimination of a tax that provides approximately $900 million in revenue to the state each year may seem extreme at first glance, legislators and the general public should seriously consider the facts, projections, and theories discussed in this report.

What Is RI-STAMP?

Dynamic Economic Modeling: There is a common and fundamental miscalculation when it comes to projecting the effects of tax policy on tax receipts. Too often, the more short-sighted and simplisticstatic (straight-line) calculation is utilized, when in reality the more complex dynamic impact should be evaluated. The downstream ripple effects of tax policy on various aspects of the economy and upon other tax receipts and fees are rarely discussed or attempted to be quantified, either at the state or municipal level. RI-STAMP seeks to fill this gap.

Developed by the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University, RI-STAMP is a customized, comprehensive model of the RI state economy, designed to capture the principal effects of city tax changes on that economy. In general STAMP is a five-year dynamic computable general equilibrium (CGE) tax model. As such, it provides a mathematical description of the economic relationships among producers, households, government and the rest of the world. It is general in the sense that it takes all the important markets and flows into account. It is an equilibrium model because it assumes that demand equals supply in every market (goods and services, labor and capital); this is achieved by allowing prices to adjust within the model (i.e., prices are endogenous). The model is computable because it can be used to generate numeric solutions to concrete policy and tax changes. And it is a tax model because it pays particular attention to identifying the role played by different taxes.[16]

RI-STAMP has been accurate in projecting the effects of recent changes to tax policy in Massachusetts and New York City, among other locales.[17]

NOTE: See the PDF version of this report for the detailed Zero.Zero projections from RI-STAMP. View complete 2012 Zero.Zero brief as a PDF; view2012 economic and revenue projections here

End Notes:

Significant portions of this report were researched and written by J.Scott Moody, an adjunct scholar to the RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity.

[1] The 2012 iteration of the report card is available at: http://www.rifreedom.org/2012/02/rhody-fails-report-card/

[2] “Rich States Poor States,” 5th Edition, ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitive Index, p vii and p 6

[3] Drenkard, Scott, “Facts & Figures Handbook: How Does Your State Compare?” The Tax Foundation, 2012. http://taxfoundation.org/article/facts-figures-handbook-how-does-your-state-compare-0

[4] Cline, Robert, Mikesell, John, Neubig, Tom, Phillips, Andrew, “Sales Taxation of Business Inputs,” Council on State Taxation, January 25, 2005, p. iii. http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CC8QFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.cost.org%2FWorkArea%2FDownloadAsset.aspx%3Fid%3D69068&ei=4BZkT_OUN-f40gH0tM2oCA&usg=AFQjCNECBZGKF7n66LYAXalSdkz1YOONXQ

[5] Crain, W. Mark, “Volatile States: Institutions, Policy, and the Performance of American State Economies,” The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2003, pp 70 & 71

[6] Phillips, Andrew, Robert Cline, Thomas neubig, and Hon Ming Quek, “Total state and local business taxes,” Ernst & Young and Council on State Taxation, July 2012.http://cost.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=81797

[7] Moody, J. Scott, “The Great Tax Divide: Maine’s Retail Desert vs. New Hampshire Retail Oasis,” The Maine Heritage Policy Center, April 13, 2011. http://www.mainepolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/VER-2-Path-to-Prosperity-The-Great-Tax-Divide-041311.pdf

[8] Woolf, Arthur, “The Unintended Consequences of Public Policy Choices: The Connecticut River Valley Economy as a Case Study,” Northern Economic Consulting, Inc., November, 2010.http://www.vermonttiger.com/files/unintended-consequences-2-1.pdf

[9] Brinner, Joyce and Brinner, Roger E., “Fiscal Realties for the States: Economic Causes and Effects,” Global Insight, Inc., 2007, p. 17. http://www.ihsglobalinsight.com/gcpath/fiscalrealities.pdf

[10] The RI-STAMP model compares the alternative tax proposals “as if” the economy were already in equilibrium. In reality, the adjustment period cannot be specifically defined; a year could be six months, or it could be 18 months. Reality also tends to have additional layers of dynamic change that cannot be predicted, from changes in other tax rates to changes in technology to changes in the population or the weather. As with any large change, contingency plans should accompany any policy decisions made on the basis of the projections contained herein.

[11] “Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States,” The Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy, January 2013. http://www.itep.org/pdf/whopaysreport.pdf

[12] For the bills’ text see: http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/BillText/BillText13/HouseText13/H5365.pdfand http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/BillText13/SenateText13/S0246.pdf

[13] “Uncovering Waste, Fraud, and Abuse in the Medicaid Program,” U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Staff Report, April 25, 2012.http://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Uncovering-Waste-Fraud-and-Abuse-in-the-Medicaid-Program-Final-3.pdf

[14] “End Corporate Welfare,” RI Center for Freedom & Prosperity, May 2012.http://www.rifreedom.org/wp-content/uploads/EndingCorporateWelfare.pdf

[15] Writing for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Claudia Sahm, Matthew Shapiro, and Joel Slemrod found that the stimulus package increased consumer spending 2.4% in the second quarter of 2008, which corresponds with the fourth quarter of Rhode Island’s fourth fiscal quarter for that year (http://www.nber.org/papers/w15421.pdf). That overall percentage may understate the effect on alcohol excise taxes for multiple reasons: (1) in the period before the money entered the economy, private-sector programs emerged to advance consumers the money earlier in the year; (2) given that the excise tax applies at the product stage before the retail purchase, stores may have stocked up in anticipation of the windfall; (3) alcohol retailers may disproportionately benefit from a sudden boost in discretionary income among the general public.

[16] For more information on STAMP, see:http://www.beaconhill.org/STAMP_Web_Brochure/STAMP_HowSTAMPworks.html

[17] About RI-STAMP, RI Center for Freedom and Prosperity, http://www.rifreedom.org/2012/04/about-ri-stamp/